On the 26th of September 1983, Earth nearly faced nuclear annihilation. Deep inside a bunker near Moscow, a single Soviet officer sat on duty. For the last five years, his nights were spent monitoring the Soviet Union's early warning satellite network, just one of several global hinge points in a game that guaranteed restless peace at best—total holocaust at worst. It's hard to speak of the general mood inside the bunker, but in the halls of power in Moscow and Washington knuckles were surely whitening. The Cold War's balancing act was nauseously teetering since the officer's stationing: both countries continued to build up their ballistic missile presence in Western Europe, America waged psychological warfare in the form of bombers flying weekly missions towards Soviet airspace only to bail out at the last possible second, and earlier that month the Soviets mistakenly shot down a Korean Air Lines flight after it had accidentally veered into Soviet airspace. All passengers were killed, including a U.S. congressman—the politburo accused the United States of trying to provoke a war.

Amidst this seemingly endless spiral downwards, the Soviet officer sat as a watchman, monitoring reams of paper readouts and lime green radars. Shortly after midnight on the 26th, klaxons blared as the command center's main terminal switched blood red. A U.S. ballistic missile appeared minutes away from impact. Now two—three?—five missiles coming to wipe out life as we know it. The officer's sole job was to report imminent nuclear strikes to the Soviet leadership, to turn the gears of mutually assured destruction. In this moment, with sirens screeching, terminals flickering “IMMINENT IMPACT”, and bloodshot eyes of panicked technicians flashing at him, he refused. The officer grimly reasoned that if this were to be the end of all life, surely it would be by a whole arsenal and not merely five missiles. Naturally, he was right. It was a false alarm caused by sunlight glancing off clouds high in the atmosphere—some highly specific condition that wasn't taken into account when scientists programmed the system.

If you're just learning about this event now, you might feel unspeakably queasy knowing that we avoided Armageddon on account of a gut feeling. Personally, I'm more alarmed that this was only the first, less convoluted brush with nuclear war in the span of three months. Although neither of these events were known by the public at the time, culture and day-to-day life were surely bathed in anxiety over instant annihilation in a way we might never fully appreciate today. The 1984 release, "Two Tribes'' by Frankie Goes to Hollywood offers us a window into pop music and culture in the age of atomic brinkmanship.

Frankie Goes to Hollywood was a five-piece group from Liverpool and a total flash in the pan. Speaking from an American perspective, I can't even say that there's a living cultural memory of Frankie. Unless you were alive and raising hell during the two years of relevance doled out to the band, your first (and likely only) encounter with the group came from tossed off jokes from Friends and Zoolander.

It's not exactly fair to label Frankie Goes To Hollywood as a British event - they did achieve a measure of commercial success stateside, something elusive to even the best anglo acts. But what if I told you that in Britain the band had three consecutive number one singles? That they were the first musical act to hold the top two spots on the UK singles chart since the Beatles in 1968? Or that their debut record went triple platinum? Frankie was absolutely a phenomenon in the kingdom, which is made stranger by the fact that in 1982 they were just five Liverpool lads playing in another twitchy post-punk band.

Holly Johnson, the most recognizable face of the bunch, came from the explosion of the rinky-dink Big in Japan: a punk band more known for who was in it (Bill Drummond of the KLF, Budgie of Siouxsie and the Banshees, and the Lightning Seed's Ian Broudie) than anything they actually accomplished. Moving from bass to vocals, Johnson would join bassist Mark O'Toole, guitarist Brian Nash, drummer Pete Gill, and all-around utilityman and dancer Paul Rutherford. True to the spirit of the scene, Johnson and Rutherford were the only members with experience in a band while the others initially tagged along. That, and they were also openly, flamboyantly gay.

Take a moment to pause and recall the known gay pop musicians of this era. George Michael, Elton John, Boy George - by 1984, these three either kept quiet about their homosexuality or chose to label themselves bisexual. Nevertheless, your average Brit could likely make out the general character of the bunch by their theatricality, sensuality, and sheer extravagance. Of Bronski Beat and Marc Almond of Soft Cell, the former were more interested in the acceptance and normalizing of homosexuality, while the latter played with general, good ol' fashioned sleaze and late night deviance. Amid the forking paths for gay British musicians, give credit to Frankie for choosing to blaze an entirely different trail; they were, in a simple word, horny.

The band's image collided Mad Max with the erotic art of Tom of Finland, meaning leather, studs, staches, and fishnets. For the cherry on top, the lads from the end of the world recruited two women - The Leatherpets - to act as on-stage dominatrixes for the pleasure of both sexes. Like any post-seventies British act with a knack for flare, Frankie's visual performance descended from Bowie and his Spiders from Mars. However, in pushing the presentation to such a extreme, it's more apt to say that they owed a debt to professional pop troublemaker Malcolm Mclaren and the Sex Pistols. It's more than mere speculation: Johnson claims that the inspiration for Frankie's image came from watching the Mclaren managed Bow Wow Wow live while tripping balls. Pop music has always taken advantage of selling love and sex. What Mclaren successfully gambled on was using the underage Annabella Lwin to play with a dying empire's confused psychosexual hang-ups. Frankie's proposition was a natural step forward: why not gay sex?

There are three documents capturing the first year of Frankie Goes to Hollywood: a session broadcasted by John Peel late in 1982, another set with Radio 1's Kid Jensen, and a low budget video shot for Channel 4's musical variety show The Tube, both debuting in February of 1983. These two radio sessions are valuable for stripping away the on-stage distractions and letting the music stand alone. What remains is passable, but nothing truly showstopping—the greatest assets being O'Toole's machine gun bass, Johnson's operatic panache, and the group's general fun, funky vibes. Both sets show a young punky band enjoying themselves, angling for any kind of commercial attention with some half-baked songs and amateur talents—there's moments of truly braindead drumming, and Nash's guitar playing is especially uninspired. Most noteworthy is the presence of their two biggest hits in early stages, "Relax" and "Two Tribes". The songs are fine pieces of sloganeering, but where "Relax" comes fully formed—deep grooved and raunchy in all the right places—"Two Tribes'' is one of those half-baked tracks, stitched together with borrowed elements: an intro aping Joy Division and a rumbling bass ripped from Bow Wow Wow's "Elimination Dancing". It's great for a Tuesday night down at the club, but you won't be surprised to know that labels turned them down left and right.

In light of the radio sessions, the video made for The Tube doesn't offer any new developments with Frankie. Their performance is tamer, but it's clearly another shot to build any kind of commercial attraction at all (do stick around until the end for a goofy interview with a young Jools Holland). If their music wasn't leading to any takers, then putting on this kind of show and broadcasting it across the U.K. felt like a dare. It's fitting then that ZTT Records would be the ones to offer a record deal, as the intentions of those behind the label were a kind of dare, too.

By the time Trevor Horn started ZTT Records with his wife and business partner, Jill Sinclair, and music journalist Paul Morley, the man had rounded all the music industry bases and was heading home. Write, record, and produce an iconic number one hit? Check. Produce a number one album in the U.K.? Check. How about a mixture of the previous two but this time in America? You guessed it. For a man being called the "Phil Spector of the Eighties", the next step was to have his own label and full control over an artist's sonic direction. But if Horn focused on producing the music, then Morley's role involved creating the label's mystique (A&R, marketing, art direction, and commissioning). Morley was a special creature of music journalism that only late seventies Britain could produce: a self-assured know-it-all, eager to intellectually drub anyone, dropping loose takes on Barthes and Foucault along the way until you submitted to his wisdom. His first act was to christen the union between Horn, Sinclair, and himself as ZTT—Zang Tumb Tuum—after a sound poem of the same name by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Italian founder of the artistic Futurist movement. In his own words, he had "...a kind of ideological commitment to making pop music stranger, cleverer, more beautiful, more surprising, and record sleeves and associated paraphernalia more entertaining and provocative." Morley was a true believer and thought pop could save the world.

As the first major signing by ZTT, Frankie finally received what the members nakedly asked for in every interview: money, attention, and perhaps some TLC. Funnily enough, this is where the people behind the band all but disappear from the story. Horn refused to let the members into the recording studio or make any public appearances whatsoever until he crafted the "Frankie Goes to Hollywood sound". To hear the producer tell it, this wasn't megalomania but sound judgement. They just weren't good enough in the studio. Instead, Horn would rework the first pair of singles—"Relax" and "Two Tribes"—using the original songs as building blocks. In no way would there be a guarantee that the results would be recognizable. For the record deal to turn into a kind of Faustian bargain mixed with Dorian Grey was totally on brand for a band like Frankie.

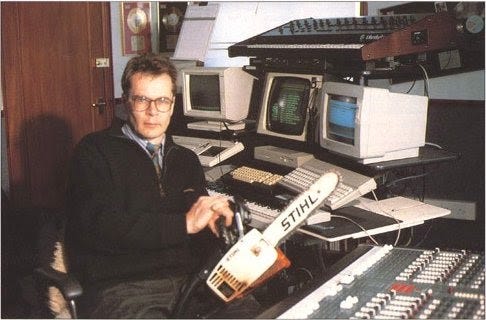

The existence of "Two Tribes" is owed to two pieces of technology, a yin-yang of destruction and creation: nuclear weapons and the Fairlight CMI. You may not have heard of the Fairlight, but much like nukes, it changed the world as we know it. With the first models made available in 1979, the Fairlight was an early digital audio workstation with one of the first built-in digital samplers. For £18,000 (or about $36,000), you could have been the proud owner of a first of its kind device that could sample sounds for a grand total of—one second. This absolutely blew minds; one of the first to be exposed to the wonder machine, Peter Gabriel immediately used it to add the sound of objects being beat to hell to his music.

Horn acquired the Fairlight in 1981, making it only one of four in Britain, and added programmer J.J. Jeczalik to his production team to work the damn thing. Alongside engineer Gary Langan and composer Anne Dudley, the quartet gently experimented with the production of ABC's The Lexicon of Love, embellishing and tweaking sounds where they could. With a full year of experience under their belts, the group then took over production of Duck Rock in 1982. In the spirit of collaborating with Mad Malcolm Mclaren, the crew went hog wild, bringing New York hip-hop—and one of the first songs ever to feature scratching—to the isles. At the same time, Horn and company were embroiled in the million dollar recording sessions for Yes’ comeback album, 90125. Stretching into 1983 and taking entirely too much time, Jeczalik and Langan spent their studio downtime fiddling with the brand new Fairlight CMI Series II (about $60,000). Sporting a first of its kind sequencer, they sampled an entire drum pattern and, well, turned “Owner of a Lonely Heart” into a bricolage dance remix in a fit of pure jamming euphoria. The result so titillated Horn that he persuaded his production team to form an actual group and affixed himself and Morley in advisory positions. As chief namer-of-things, Morley dug back into his bag of futurism and titled the project The Art of Noise.

It was around this period that Horn literally pinned a Jolly Roger over his Fairlight, and if it didn’t cause rolled-eyes it was only because his team was honestly making revolutionary music with “stolen” sounds and studio time. Still in the midst of the 90125 sessions, The Art of Noise continued to pick up the scraps and detritus from Yes’ largess and built experiments that reflected their last year of work in production. In the vein of Duck Rock came “Beat Box”—sounding like it pop-and-locked straight out of a Bronx alley, orchestral stabs and all; more meditative and dripping with a kind of prog sentimentality was “Moments in Love”. Both songs, as well as others collected on 1983’s Into Battle with the Art of Noise, were statements of intent—with new technology and new notions of what would be possible, pop music was going to get a good warping.

It makes sense that Horn would be eager to sign Frankie Goes to Hollywood—besides being just a nice set of lads, the quintet was as close to a blank slate as you could muster while still willing to play ball. Of course, it helped that their contract handcuffed the group to the proverbial bed, leaving the whole of ZTT free to tease and play with their own notions of pop and the pop group. However, in order to unleash something new, all involved would need to lean on the comforting and familiar in culture: sex and violence.