On the count of three, the five members of Frankie Goes to Hollywood cannonballed into a pool behind a 17th century manor in Oxford. It was July of 1983, just two months after the band signed with Trevor Horn and ZTT Records. Since their first gigs on Liverpool's underground circuit, Frankie had been panting after any kind of record deal—after any kind of action at all. Now with a producer responsible for multiple number one records on both sides of the Atlantic, they would surely be in the money now.

In reality, the lads from Liverpool were utterly screwed. Masterminded by Horn's wife/business partner, the contract promised a nearly $500 advance for Frankie's first two singles along with a meager 5% royalty rate. That Oxford manor was a recording studio where Frankie initially attempted to set down "Relax". Every session ended as a complete dud, leading Horn to exile the band from the studio until further notice. Not even allowed to perform publicly until the label crafted their new sound, the only contribution from the band en masse for the next four months was . . . jumping into the pool. J.J. Jeczalik recorded the sound for future contortion on the Fairlight.

The creation of the ZTT-ized "Two Tribes" was a carbon copy of the process behind "Relax". In short: spend entirely too much time and money to warp a simple post-punk tune into a lush digital landscape. Of the two, "Relax" is only slightly more storied. After the aborted session in Oxford, the producers reworked the track three separate times in the studio over the course of nearly four months. Interestingly, Horn and his crew weren't originally committed to a complete digital makeover of Frankie. The first attempt involved hiring a different band entirely—The Blockheads minus singer Ian Dury—to fill out the backing track. Perhaps what they had in mind was more of an airbrushing in the vein of their work on ABC's Lexicon of Love. The new musicians were certainly more competent, but they apparently missed the sexual bravado necessary for the song's spirit. This led Horn to give up on session musicians altogether and lean on his producers, including newly hired engineer Steve Lipson and keyboardist Andy Richards.

The second rework was a nightmare. Taking Frankie's original demo, the producers broke it down into its primary sounds and went about a full digital reconstruction. Not much is out there describing exactly what this meant, but the efforts and results were described as "torturous" and "rubbish". If I had to guess, after the free-wheeling sessions with Yes, Horn and company were used to a single-minded pursuit of perfect sounds—Richards was told to focus on constructing an earth-shattering orgasm on his Jupiter-8 synth, for God's sake. There’s no doubt about Horn’s innate perfectionism, and the pressure to ace his label’s first release only exacerbated the issue. Meanwhile, as The Art of Noise, J.J. Jeczalik, Anne Dudley, and Gary Langan were still busy building their first record. Released a full month before “Relax”, Into Battle with the Art of Noise suggests another explanation for ZTT’s struggles: the music and tech were still being figured out along the way. What else does the first attempt with the Blockheads show if not a reluctance to embrace pure technology? Into Battle’s highlights are conceptual documents, exploring the limits of their synths and samplers without the restrictions of verse-chorus-verse. I can only imagine that the attempt to distill those ideas down to a sub-four-minute pop song drove everyone up the wall. The languid pace of their sessions with Yes allowed for such experiments, but where Horn and The Art of Noise were previously playing with house money on 90125, the costs of "Relax" piled up to nearly $50,000 of ZTT’s cash.

“How much did we spend on that orgasm?”

Three weeks into recording, the call was made to trash the sessions and start over—not out of despair, but rather clarity brought on by a huge lump of hash Trevor Horn smoked one night. His gang on hand were great musicians in their own right, so why not let them take a crack at it? Building from one of Horn's pet drum machine patterns, Jeczalik, Lipson, and Richards sat down and took a swing with one big jam. Naturally, they nailed it. The rhythm track was finished after a couple hours and at 4am, stoned and bleary-eyed, Holly Johnson shuffled into the studio to add his vocals. Save for overdubs, the song was completed that night. Depending on who you ask, the final cost sat anywhere from $52,000 to $140,000.

“Two Tribes” presented an entirely different challenge for ZTT’s producers. For one, it wasn’t a proper song. Listen to their late 1982 performance on John Peel’s radio show and what do you hear? A jingle at best, backed by players who sound like they’re combining three different songs. The demo recorded by Frankie had zero direction. You might think Trevor Horn either a visionary or insane to follow a number one, platinum hit with something so half-baked. It wasn’t genius, but a matter of necessity: there just weren’t any other promising songs. On the bright side, the decision offered a chance to appear thematically coherent. How else do you follow capital S-E-X? It needed to be a song about war—about violence. Besides, god damn, what a bass line! So much for the rationale, though you have to feel some sympathy for his employees. Months of “Not quite right”, “Too much”, and “Just not enough” with “Relax”, and now this? Perhaps they found solace in thinking they now had a method, that they’d finish the single quicker.

These sessions would drag for another three months. Working on the bass alone took weeks; Steve Lipson later remarked how, working in a separate studio down the hall, production duo Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley finished mixing one album, then recorded and mixed Elvis Costello’s Goodbye Cruel World in the same time it took Horn’s crew to land on the right tone. It wasn’t only a matter of endless tweaks—flush with confidence (and money) from the success of “Relax”, they were motivated to add whatever necessary to unify and elevate the song. Part of the shock and awe campaign included Anne Dudley conducting a sixty piece orchestra, bringing much needed dynamics to the digital sound. There was also the matter of potentially breaking the U.K.’s Official Secrets Act.

The Cold War reached its stomach churning peak in 1983-84. Between the ridiculous proxy war in Afghanistan, Able Archer’s aftereffects, missile deployments in Western Europe, and the peak of the Soviet nuclear production, you could easily imagine tasting isotopes in the air. Those who recognized the ill omens joined several anti-nuclear peace organizations, of which Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament became Britain’s largest with nearly 110,000 members in 1985. Sensing the general paranoia and thinking “Why not add more?”, the British intelligence agency MI5 considered these individuals subversive pinkos under Soviet control and regularly scrutinized these organizations. Their tactics: wiretapping, double agents, and red baiting in the media.

While the kingdom no longer steered the course of global politics, Margaret Thatcher’s government made itself an easy target for activists. Following in lockstep with the Americans, Thatcher helped campaign for the new round of missile deployments on continental Europe, gratefully accepted the stationing of US cruise missiles in Britain, and spent billions to buy a new submarine nuclear launch system. The ghost of the empire wouldn’t stop rattling its chains either: Britain’s involvement in the 1982 Falklands War was purely for the defense of colonial acquisitions—to not look weak—leading to a swell of national pride that carried the Conservative government through to a landslide victory in the general election of 1983. We can look back and see that these dots never connected to anything, never resulted in the rebirth of an empire double-fisting warheads. But to be alive then, to feel the spirit of the times, it must have seemed like the whole damn world had gone mad. Try sleeping at night when you know that the tiniest argument between diplomats could escalate to apocalypse.

It’s not clear whether the band’s management inquired or if CND felt an opportunity to use Britain’s hottest act as a vehicle, but members of the organization passed onto Trevor Horn and Paul Morley a copy of a secret government film that was to be publicly aired in the event of a likely nuclear strike. “Likely nuclear strike?” Yes, the British government felt they might have at least a three day notice and would air the film then. Called Protect and Survive, it gave instructions like: make sure your curtains and doors are firmly shut, and: remove your doors to build a lean-to to hide your family from fallout. I can’t claim to know the politics of any of the ZTT producers—I imagine they each took the admirable stance of anti-annihilation. What I do know is they approached this tape like any other recording professional with sampling technology: as a gold mine. One problem—anything lifted directly from the film would be considered a violation of the Official Secrets Act. It’s one thing to have your music banned by the BBC, but committing a felony when the government is targeting activists? Hell, doesn’t this all sound like a honeypot? Horn and Morley found a loophole of sorts by enticing Patrick Allen, a familiar actor and the narrator of Protect and Survive, into the studio and giving him free rein to repeat his narration. This included all the lines that were nixed as too grim for an upbeat PSA about surviving nuclear armageddon.

The effort by ZTT elevated the song from open-mic night at The Factory to something more akin to a biblical struggle with a dance beat. For all the talk of the label hijacking Frankie’s music, what’s remarkable about 1984’s “Two Tribes” is just how true it remains to the song’s original structure. Mark O’Toole’s bass was the propulsive heart; now it’s dropped an octave, chopped up, and fed to an array of samplers and sequences to reach a massive, blocky sound. It brings to mind green, flashing 1’s and 0’s, supercomputers chugging away in a command center, trajectories and impacts being mapped. The original drumming is thrown out in service of a danceable 4/4 kick, but the fills are replaced with heavier flourishes of digitized snares and cymbals—my favorite being the added element of some kind of bongos or tribal drums floating around the edge of the mix. Even the dirgey intro and pointless, silly bridge are saved by the grace of Anne Dudley’s orchestra. The former becomes pure melodrama, a soundtrack to a cavalry charge straight into howitzers—have you ever noticed how well air raid sirens pair with strings and woodwinds? In the middle of all the bombast, the bridge now gives a sprinkle of levity. It gives a knowing wink towards the comedy of Frankie putting out a message so strident after singing in their last song “Ow ow ow ow, I’m coming, I’m coming—YEAH!”

Neither should Holly Johnson’s performance be undersold. Viewed one way, the Trevor-ing of Frankie Goes to Hollywood was in order to bring the music up to Johnson’s level; this guy is made for the overblown. His delivery is best described as opera with a sneer. Nearly every time something slashes through the mix, whether it’s Steve Lipson’s guitar licks, triggered explosions of percussion, or live orchestra stabs, Johnson meets the intensity by either laying on extra vibrato or giving the most engaging funk scat this side of the Atlantic. It’s all very exhilarating, and thank god for it because the lyrics are just plain dumb. Yes, the chorus is memorable and delivers a fine sentiment, but then there’s some kind of allusion to Reagan, something about loving and good times, and . . . yeah. The song’s last thrilling burst is centered around Johnson asking “Are we living in a land where sex and horror are the new Gods?” It’s a line straight out of the film Network—playful and ironic in light of the reaction to “Relax”—and delivered with enough relish and disgust to make you forget that the last lyric was “Sock it to me biscuits”. Nothing here is subtle—but then again, neither is nuclear war and dancing.

Released in Britain in the last week of May in 1984, “Two Tribes” sold half a million units in two days and charted at number one the next week. It would stay there for nine weeks, longer than any other number one single of the 80’s in Britain. Even “Relax” felt the ripples, as it buoyed up to number two after nearly dropping out of the UK Top 40. That the reaction is more muted in the US (peaking at 43 on the Billboard Hot 100) cemented Frankie as—“European”. The song’s quality speaks for itself, but the marketing of the single and the band was just as responsible for its wild success. Paul Morley was a pure provocateur, just as willing to write pseudo-intellectual liner notes about sex as he was to commission an ad announcing “ALL THE NICE BOYS LOVE SEA MEN”, and “MAKING DURAN DURAN LICK THE SHIT OFF THEIR SHOES”. Nothing was fundamentally new in this approach, and now nearly forty years removed, this style of advertising through shock value feels more common and worn down. But even by modern media standards, Frankie put out genuinely outrageous statements. Take the music video for “Relax”. Sure, there’s plenty of metaphors to be had about journeying to the underworld and facing your darkest desires, but you’re also given drag queens writhing around in cages, a fat Caesar stripping down to his bare ass, and thinly veiled references to golden showers and water sports.

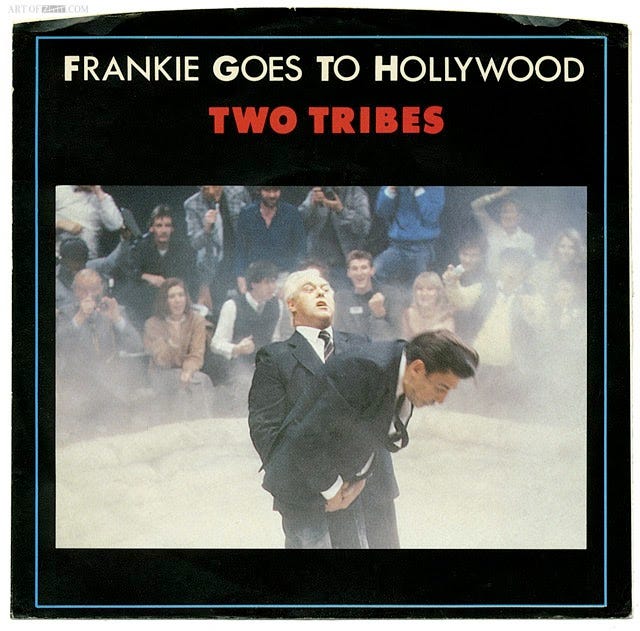

“Two Tribes” didn’t require that level of excess to create a cultural buzz—Morley’s shenanigans and the BBC banning “Relax” from public airwaves handled most of that. Even so, Morley doubled down with piggybacking on a political issue. An ad was designed with a table listing the effects of a nuclear war fought with one-third of the US and USSR stockpile; above it reads “HANDS UP, WHO WANTS TO DIE?” Photographed by Anton Corbijn, a mural of Lenin appears on the cover of the record sleeve. The back is filled with Morley’s digressions—focused on war this time—and two more tables: one detailing the American and Russian arsenals, the other laying out which western European countries were receiving new missile deployments (all provided by CND). Then there’s the matter of the music video. After the last one, you’d might expect impersonators of Ronald Reagan and the Soviet Premier having sex in a UN bathroom. But no, they’re only bare knuckle brawling in front of a braying mob of gambling diplomats and reporters. Reagan nearly bites an ear off, then the planet explodes.

FGTH as innovators: 13 years before Mike Tyson did it

Sales of the single were also maintained by the various remixes that ZTT released throughout 1984. “Relax” used a similar strategy, which resulted in the 16 minute “Sex Mix” and, after gay clubs complained about some of its more disgusting noises, a shorter derivative. It wasn’t just one or two mixes for “Two Tribes”, though. Try at least six different versions on 7”, 12” and picture disc, all with such titillating names—”Cowboys and Indians” (the original 7” single), “Annihilation”, “Carnage”, “We Don’t Want to Die”, “Hibakusha”, and “For the Victims of Ravishment”. Releasing a legion of remixes was just one more piece of new ground broken in the music industry by Horn and his producers (and yet another testament to Horn’s runaway perfectionism), but it’s a shame to say that only two or three versions are worth your time. The “Annihilation” mix is the song in full club form; just over nine minutes, it opens with droning sirens, adds long percussive solos and breaks, and features extended readings from Patrick Allen on how to properly dispose of a dead, irradiated grandmother. As far as the best pop mix, nothing touches the energy of the original release. The version on Welcome to the Pleasuredome comes close, but does the unforgivable by removing the magical, Loony Tunes bridge.

Anti-war songs come and go, but what exactly makes “Two Tribes” stand the test of time? It’s certainly not the most emotionally affecting, nor would anyone go out of their way to call it poetic. Regardless, I’d argue it has just as much artistic worth as Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall”, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On”, or Kate Bush’s “Breathing”. The real virtue of the song lies in its simplicity and directness, in how it doesn’t lecture or bother with some grand statement. Death, let alone nuclear war, is something unfathomable. Most of the best minds among us can’t grasp the thought of everything disappearing in a flash. Why bother dressing it up? Similar to Prince’s “1999” from two years earlier, “Two Tribes” instead gleefully suggests abandoning yourself to dance. You might accuse the song of being too playful or silly with such a grave matter, but that’s the whole point. Frankie, ZTT, and Trevor Horn wrung joy out of doomsday in a way that no other 80’s pop act could copy.

While Frankie Goes to Hollywood remains a brief and unremarkable footnote to America in the 80’s, the band owned the full attention of the UK for a whole year and still exists as an example of the vitality of pop music. Strange, gross, and wonderful things came out of the meeting of hardcore studio wizards, enthusiasts, and total amateurs. What Trevor Horn, J.J Jeczalik, Anne Dudley, and others did with their technology showed just how vibrant and entertaining music would become in the face of Moore’s Law over the next thirty years. If Paul Morley didn’t exactly prove that music can save the world, he at least demonstrated the power of music marketing that treated listeners as people looking for fresh, provocative art, not dead-eyed consumers. As for Frankie—Holly Johnson, Paul Rutherford, Peter Gill, Mark O’Toole, and Brain Nash—they certainly shot their shot, didn’t they? After releasing Welcome to the Pleasuredome, the band self-destructed from internal friction, an awful label deal, and a universally ignored sophomore album. The five rose up from the depths of Liverpool to the peak of pop, then scattered back down to obscurity. They were Britain’s own Homeric myth of the 80’s, war, homoeroticism, and all.